12 July 2019

|Sex / Gender

Diversity / Inclusion In Practice

Women’s Rights

Women as Queen’s Counsel: why are numbers so low?

Key resources:

-

Farore Law: 2019 Report on the slow progression of women in the professional spheres

-

The Lawyer: How gendered instructions at the employment Bar are scuppering female barristers’ ambitions for silk

The title of QC identifies lawyers who have demonstrated excellence in their fields of expertise. The substantial majority of QCs are barristers, and it is up to each individual whether or not to apply for QC status.

Significantly fewer women than men apply for QC each year. Since data collection began in 1995, the number of male applicants has been recorded as consistently (and considerably) higher.

This discrepancy exists in spite of the fact that women tend to outperform men when it comes to successful applications. Take for instance the 2018 application rounds: the number of female and male applicants were 55 and 186 respectively. Yet, 54.5% of female applicants were successful, compared to 41.9% of men. This was much the same a decade ago: in the 2008-9 application round, 29 women and 215 men applied. Yet, 55.2% of females were successful, compared to 40.5% men. [1]

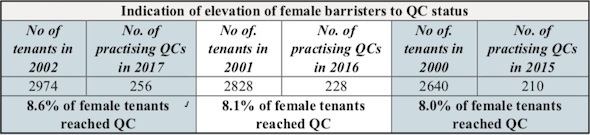

The BSB has yet to break its figures down by practice area, but it is clear that there is an extraordinary lack of representation of women at QC level. Farore Law has noted that the current percentages of successful women applicants do not reflect the increase in the number of women barristers practising in the preceding 15- to 20-year period (15 years being an ordinary amount of time in practice prior to application). [2] Our report analysed two sets of data to produce the following table, which provides a comparative (if rough) indication of the total percentage of women who attained QC status after 15 years of practice across a 3-year period: [3]

This begs the question: why are numbers so low? Interestingly, a recent article produced by The Lawyer looks at the QC gender problem from an employment law perspective, and considers whether or not it is the result of a system that actively works against female barristers. [4]

The QC gender problem: an employment law perspective

In 2018, only 5 out of 38 QC applications were made by women in the employment law field. A special meeting was subsequently held at the Employment Appeals Tribunal (“EAT”) in October that year, headed by Dame Ingrid Simler QC (the former President of the EAT) and Her Honour Judge Jennifer Eady QC (Senior Circuit Judge at the EAT). Women were invited to discuss their experiences applying for QC.

The result of the meeting was clear: the problem of low female applicants is not simply because women are neglecting to put themselves forward. Rather, for those female barristers interviewed by The Lawyer, it appears to be a consequence of female barristers not being assigned the same level of cases as their male counterparts. This in turn impacts their ability to secure the necessary experience and exposure expected of QC applicants.

A mid-level junior barrister at a leading commercial set commented: “Men do the sexy, big-money high-profile well-paid cases, while women do washing-up law […] This is gender segregation by work type and is a wider problem in the profession.” Rebecca Tuck of Old Square Chambers confirms this concern: “There are quite a few levels before a brief gets to us and women barristers potentially face discrimination when getting instructions from solicitors, clerks and lay clients […] As you go through the years of call, it becomes increasingly difficult.” [5] Suzanne McKie QC, Founder of Farore Law, commented that the firm has received and dealt with a number of concerns expressed by senior barristers regarding the allocation of work along gender lines in a variety of chambers, and that this does give cause for concern.

The issue of women being provided with “‘housekeeping work’ rather than ‘glory work’” was illustrated as particularly relevant to female barristers by the Law Society in 2019. [6] According to a member of the judiciary, it is “obvious” that women at the Bar are “simply not being given access to the lucrative work”. [7] This sentiment has been repeated by Lady Hale, President of the Supreme Court: “I have heard from very competent women barristers that they don’t feel they are getting the big cases that their skills and experiences deserve when compared with the men.” Lady Hale also indicated that women were being “charged out” by their clerks at a lower rate than men, despite their comparable seniority. [8]

Fresh data analyses conducted by The Lawyer

The Lawyer conducted an analysis into the gender gap at the employment law bar following the October 2018 meeting. This analysis addressed data relating mainly to the EAT and employment law cases at the Court of Appeal between 2015 and the start of 2019 inclusive. As the results show, the conclusions of the October meeting are not without considerable merit.

Employment law may be a “relatively feminised” area, but The Lawyer’s analysis shows that the EAT is male-dominated. 15 female QCs represent 2.5% of the total number of barristers active in the EAT. 74 male QCs represent 12.8% of the total; 159 female juniors represent 27.5%. Yet, it is the 329 male juniors who are instructed for 57% of work at the EAT. To quote the article directly: “The gender disparity in court work from the junior end, as barristers begin to forge their careers, immediately makes itself clear.” [9] This is not a promising insight into the future number of women QCs.

The Lawyer acknowledges that barristers’ work is usually directed to them via their chambers, meaning that gender patterns “vary dramatically from set to set”. Accounting for this, it found that female employment barristers are more likely to appear in the EAT and Court of Appeal if they have tenancy at Cloisters. The Lawyer notes that a “striking” feature of Cloisters is its “relatively high female demographic”: 4 out of its 15 QCs are women, as are 19 of its 38 juniors. Cloisters also enjoys near-parity amongst its junior barristers: 18 male juniors and 15 female juniors were active within the assessed time period. The Lawyer draws in Littleton by way of comparison, which has the highest gender disparity out of the 5 busiest sets at the EAT. Only 1 of the 14 QCs at Littleton is a woman, following the departure of Farore Law’s founder Suzanne McKie QC. 9 out of the set’s 40 juniors are women.

According to The Lawyer, it is Cloisters’ recruitment policy that made the difference: the set monitors trends in work allocation by protected characteristics (including sex), and takes action as and when concerns arise.

The Lawyer also found that claimant firms tend to opt for male QCs at the EAT. A total of 27 QCs were instructed by the top 10 most active law firms in the EAT during the analysis period. Of those 27, only 4 were women. The analysis also found that men receive the majority of instructions at the Court of Appeal, within which women act mainly for claimants. 244 barristers in total were involved in the 136 employment law cases identified at the Court of Appeal during the relevant timeframe. Of those 244 barristers, only 56 were women (23%). Only 10 of those 56 women were QCs. (Compare this to the 188 men involved, 67 of whom were QCs.) The Lawyer notes that there is “a clear pattern” amongst the most active law firms in the Court of Appeal when it comes to instructing counsel: “… while these firms do give work to female juniors, they consistently opt for male silks.” [10]

Charlotte Proudman of Goldsmiths Chambers states that there is “an unconscious or maybe even a conscious bias towards men.” [11] There is much to be said for this perspective. Take the 2017 article by Chris Hanretty and Steven Vaughan cited by The Lawyer: the occurrence of single-gendered counsel teams happens “more frequently than can be accounted for by chance.” Regardless of the influence exerted by clerks, law firms, or senior/junior barristers regarding Court of Appeal cases, the overwhelming number of male QCs points to more opportunities for male juniors. Given that appearances in the higher courts can be a significant factor in applying for QC, the number of female barristers operating within them is a pertinent point.

Our comment

To reiterate our findings, there is an astonishing lack of representation of women at QC level in general, and the current percentages of successful women applicants are not reflective of the number of women barristers in practice. We also found that the progression of women at the Bar has been considerably slower than it could have been when compared with the gender balance in the accountancy and medical fields. [12] Indeed, more women appear to be applying to be judges than QCs, resulting in an insufficient number of senior women in the profession.

The fact that this disparity is being reinforced by barristers’ chambers themselves is an unacceptable situation. But, as The Lawyer correctly identifies, it is not sufficient for chambers to simply highlight female talent. Both chambers and law firms must make an active effort to promote and nurture their diversity policies in order to fully address the QC problem. This applies across all practice areas.

Farore Law has particular experience in identifying and resolving diversity concerns within barristers’ chambers and law firms. Our assessment methods account for the self-employed and highly variable nature of the Bar in particular. If you represent a set or law firm that is seeking to improve its diversity policies, please contact us in full confidence to discuss your needs.

References

[1] Farore Law Report, Appendix 1; Chart 1 sourced from the BSB’s ‘Diversity at the Bar’ report (2018)

[2] Farore Law Report, p.30

[3] Farore Law Report, p.16-17

[4] The Lawyer

[5] The Lawyer

[6] Women in Leadership in Law report: The need for gender equality in the legal profession (see p.18)

[7] Women in Leadership in Law report: The need for gender equality in the legal profession (see p.18)

[8] Baroness Hale: Women barristers miss out on big cases to men

[9] The Lawyer

[10] The Lawyer

[11] The Lawyer

[12] Farore Law Report (see p.48 for an overview of this comparison)